All that remains... The Teenagers of Socialism presents a young generation of artists from Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and the UK exploring ‘all that remained’ once the political system of their childhood had disintegrated.

In relation to the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the exhibition seeks to address the complexities of the effects of the decline of Socialism in Eastern Europe, which has been disruptive - if not traumatic - for a generation of artists who were in their mid and late teens when the first bits of crumbling concrete sparked an avalanche of revolutions in Eastern Europe. This young generation of ‘Socialists’ had to transform into ‘Capitalists’ in the midst of their adulthood. For some of them socialism became a ghostly figure linked to childhood memories, social relations and oral history - living images glued into memory like photographs in a family album.

The exhibition will showcase works, many of them previously unseen in the UK, from a variety of artists based in both the East and West countries: Anna Baumgart (Poland), Florian Wüst (Germany), Gerda Leopold (Germany), Łukasz Ronduda (Poland), Ştefan Constantinescu (Romania and Sweden), Tereza Bušková (Czech Republic and UK) and Karen Mirza and Brad Butler (UK).

Exhibition curated by Maxa Zoller.

13 March - 25 April 2010

Private view: Friday 12 March 2010, 6.30-10pm

- Phoney Language

A screening of artists' film works, curated by Florian Wüst and Maxa Zoller - What will the next revolution look like?

A performance by Karen Mirza and Brad Butler

What kind of political subject does a regime shift produce? Where does this subject position itself once it enters the new political, economic and psycho-social habitat? How does the castration of power affect desire? How long does it take to swallow a war, or a revolution? The exhibition All that Remains… the Teenagers of Socialism presents the work of eight artists from Eastern Europe, Germany and Britain, who were in their teens when Polish Solidarity sparked an avalanche of local revolutions in Hungary and East Germany leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the subsequent collapse of Communism in Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and finally Romania. The 20th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall last year marked a turning point as the teenagers of Socialism finally allow the past to spill over into the present. Did something tangible remain from this past and if so what it its potential?

These questions are particularly poignant for Ştefan Constantinescu who left Romania for Sweden in the 1990s, but was invited to represent his country of birth at the 2009 Venice Biennale. Constantinescu is an eclectic artist working in a range of media including painting (he trained as a classical painter of the Socialist Realist school), installation and video art. One of his recent works is the pop-up book The Golden Age for Children. In this ‘children’s book’ Constantinescu’s childhood memories pop up from the past and tell the reader, with gallows humour, the tale of biopolitics under Nicolae Ceauşescu’s regime. The first page introduces the reader to birth control strategies in 1960s Romania and relates this to Ceauşescu’s public condemnation of Moscow’s crushing of the Prague Spring, which earned Romania its maverick status amongst the Warsaw Pact countries. Ceauşescu’s psychological mind game with the Romanian people as well as the West, which ended in the first televised revolution in December 1989, is deeply inscribed in Constantinescu’s practice: in his short film Troleibuzul 92, which will be shown at the special screening Phoney Language, language becomes a weapon, a crime – a metaphor for oppression.

Ştefan Constantinescu, The Golden Age for Children, 2008

pop-up book, edition of 15

This exhibition presents a wide range of formally and conceptually diverse work. How does The Golden Age for Children relate to Tereza Bušková’s Spring Equinox if not by absolute contrast? Bušková is ten years younger than Constantinescu (she was eleven years old when the Velvet Revolution brought down the Iron Curtain) and like Constantinescu she left her home country in the 1990s. In her photographs and films Bušková returns to ancient Carneval and folklore rituals of Eastern Europe. Spring Equinox presents the surreal spring celebrations of the Moravian people, an ancient Slavic culture in the East of the Czech Republic. If Communism betrayed the modernist utopia of communal life it is as if Bušková has found it in the myths of pre-Socialist rural traditions. Is the return to these rituals a symptom of post-Wall political ennui? Despite their differences, Constantinescu and Bušková’s works carry the DNA of Eastern European art, Romanian DADA and Czech Surrealism respectively.

Tereza Bušková, Spring Equinox, 2009

HD video, 2-screen installation

If the artist sees the world as a stage what then is the role of theatre? The artists in this exhibition re-arrange, hide and unwrap the settings and props of our world (as stage) in order to free up established patterns of values, hierarchies and meaning. Łukasz Ronduda’s video work complicates this game even further. Cameo is in fact not an artwork, but a ‘curated exhibition’. The clips present cameo and extras performances by famous Polish avant-garde filmmakers, such as the members of the Łódź Workshop of Film Form whose co-founders Józef Robakowski and Paweł Kwiek amongst others created radically abstract works in the 1970s. Cameo also features the Polish artist Zuzanna Janin in her role as Majka from the Polish television series Madness of Majka Skowron, which became the starting point for her new video work (see Phoney Language). Originally presented as a single screen projection, Cameo has been changed into a video installation specifically for this exhibition. Could we interpret Cameo as an ironic comment on the autonomy of the avant-garde artist, who for financial reasons becomes a ‘collaborateur’ with those powers that his practice seeks to undermine? Or does it rather point at an erosion of cinema’s coded language through the artist’s masked infiltration into the system? Ronduda’s interest in Polish experimental film of the post-war period, which resulted in major publications and pioneering exhibitions and film programmes, is symptomatic for the generation of the teenagers of Socialism: rigorous historical research becomes a form of sublimation for a repressed history.

Łukasz Ronduda, Cameo, 2009

video, 13'28"

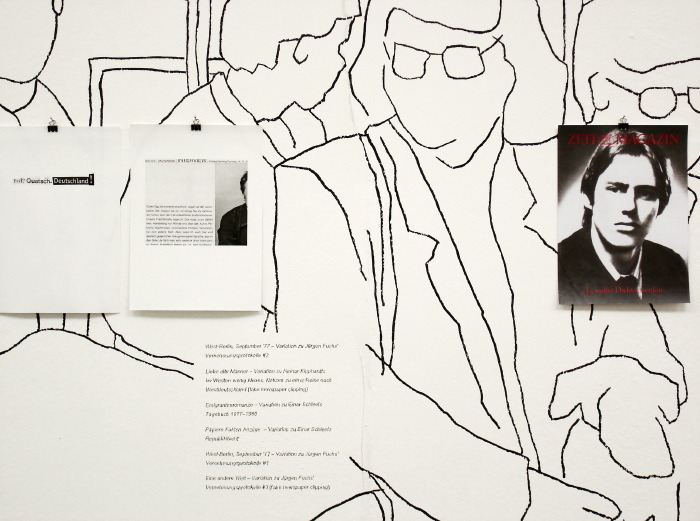

In this regard Cameo is an echo of my own practice and research, and by extension, of this exhibition. This show has in fact grown out of a film programme entitled Generation Berlin Wall: Experimental Film from East Germany and West Berlin in the 1980s presented in London last November*. One of my collaborators was the West German-born Florian Wüst, who, like Ronduda, is one of the leading film curators in his country (we curated Phoney Language together). What links Wüst’s curatorial projects with his artistic work is a research-based practice that delves deep into the archive of history. In Oberwasser (which translates literally as ‘the water on top/on the surface’ meaning In Dominant Position) Wüst opens the files of the past in order to reconstruct the present. In his large wall drawing anonymous persons wait in a queue or rummage through heaps of files, arguably STASI files. What first appears to be loose sheets of paper flying through the centre of the drawing is in fact a reference to the bats in Francisco de Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. These little monsters who according to the Latin root of the word ‘monstrare’ have come to warn us. Of what is evident: Wüst’s doomed scenario of contemporary surveillance society becomes the backdrop for a series of text collages consisting of fake newspaper clippings and extracts from literary texts by the East German authors and theatre-makers Einar Schleef and Jürgen Fuchs. In one of the extracts the latter describes his forced emigration from East to West Germany not as a liberatory journey, but as a transportation from one system to another. With an enormous appetite the capitalist free market economy swallowed the so-called ‘Eastern Bloc’, but as the former digested the latter in its gut, its own body merged with the enemy’s. In order to mask this change the remains of the German-German past have been eroded quickly and efficiently. Today Berlin is a city of absent ruins. But without a memorial there is no ritual, and without a ritual there is no mourning and no remembering. Twenty years after the re-unification, however, a new generation of artists start to dance with the ghosts. Their art is their embrace, the touch between the virtual image and the physical present.

Florian Wüst, Oberwasser, 2009

wall drawing, laser prints, dimensions variable

In Gerda Leopold’s film Mauer (Wall) a young German artist paints a wall in his Berlin ‘Hinterhof’ in a rather naive attempt to reconstruct Berlin’s most famous absent ruin. As he is challenged by amnesia (the concierge) and the claim to indexical reality (the photographer) he turns into a white-faced clown, the ancient messenger of truth. The presentation of the film in an especially designed light box adds a further dimension to the work: Leopold, who had moved from Austria to Germany in 1979, was part of Berlin’s underground art scene in the 1980s, who often used the Wall as a “giant canvas”. Her film is an homage to the experimental, interdisciplinary practices of Berlin’s Super-8 filmmakers, a subtle play on this generation’s relationship to the Wall and a re-investigation of Berlin’s changing history.

Gerda Leopold, Mauer, 2008

video, 10'30"

installation view

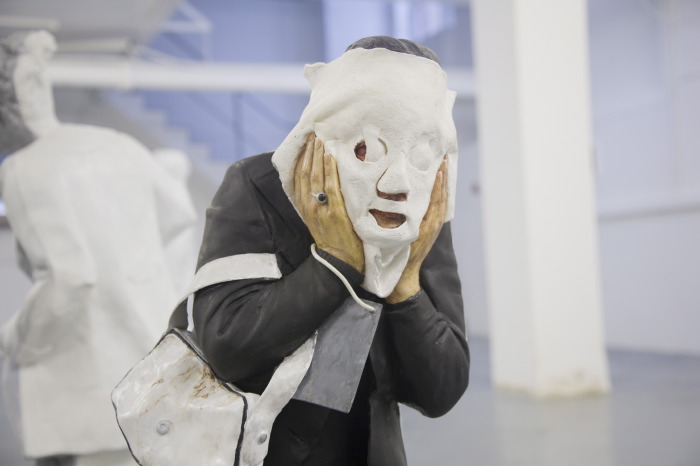

Like Leopold, Anna Baumgart is highly suspicious of the relationship between memory and the photographic image. For the Polish artist the photographer is a thief: once she has gathered the image in the frame she shoots it quickly before it escapes off into the ‘hors-champ’**. However, in her installation Hypothesis of the Stolen Image the unruly image gets back on its feet and starts to run. Baumgart’s uncannily small sculptures are based on the famous press photographs of Germans escaping East Germany at the time of the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. Taking the title from Raul Ruiz’s legendary 1979 film, which was based on a script by the philosopher Pierre Klossowski, Baumgart investigates the construction of memory through the image. Yet, an intruder breaks into this situation: this exhibition deals with the fragile history of foreign countries, but what do we feel when Britain’s trauma is turned into art? How thin is the skin between the experience and its image?

Anna Baumgart, Hypothesis of the stolen image, 2006-08

The British artists Karen Mirza and Brad Butler test the liminal threshold between reality and its fetishisation through the image. Their performance What will the next revolution look like?, which was first presented at the 2009 Werkleitz Festival in Halle, Germany, has been re-adapted especially for the context of this exhibition and will be presented at the finissage on the 11th of April. The performance is part of the artists’ ‘opus magnum’, The Museum of Non Participation. The concept of The Museum of Non Participation developed in a moment of crisis: during an artists’ residency in Islamabad, Pakistan, in 2007 Mirza and Butler witnessed the Lawyers’ Movement riots at first hand. Watching the violence unfold from the window of one of the most disputed nude exhibitions in the National Art Gallery, the city outside and the gallery inside transformed into sites of confrontation. Sandwiched between these two manifestations of protest, and thus perceiving their world from an ideological ‘non-place’, the artists started to think about how to translate this (absurd) experience into their art practice. So, returning to the questions raised at the beginning of my address to you, dear visitor, I would like to ask you: what kind of form can grow in this ‘non-place’, this interface? What kind of subjectivity can develop in this ‘infra-thin’*** space? These questions already contain their answers. In my memory of growing up in West Germany in the 1980s, German identity, the ‘I’, the first person singular, was a superfluous, an excess. Like the flesh of a lemon the personal was that which remained after the squeeze; it was the overflowing spill that was pushed out under the massive weight of an unspeakable past and an unbearable present. In a personal act that is political, I place this ‘I’, this excess – subjectivity – at the centre of this exhibition.

.jpg)