What we call ‘progress’ doesn’t necessarily take the direction we expect. Sometimes, in an attempt to ‘modernize’, the march of society pulls the rug from beneath our feet.

In their two-man exhibition, Marcin Dudek and Ben Washington create parallel large-scale installations. Both artists pick up on the need to ‘push forward’, the need to dig or climb, but also the dangers of being swallowed up or lost in the clouds.

Marcin Dudek’s work takes as its inspiration the town of Katowice in Polish Silesia – in the 1970s, a model industrial city, with high-rise architecture springing up from the work of the coalmines underneath. Excessive exploitation (or over-mining) undermined this success story, and the ground has opened up, slowly swallowing the city. Using little more than cellophane and tape, Dudek’s tunnel installation leads us into the hollows of the earth, with traps of light, sound and video.

Ben Washington’s sculptures – precarious, unbalanced objects – emerge from the sink-holes and the rubble. Suspended underneath, Washington’s works bring attention to the structures and systems that keep our environments and landscapes in the orientation we have become accustomed to: the right way up. The sculptures are at once architectural models, abstract mountainscapes, floating cities and stellar systems, and bring together the Monolith, video games, and holiday snaps from Costa del Sol.

This underground utopia - a cross between the nuclear shelter and the hanging gardens - allows us to inhabit the man-made and the natural at the same time. From here, in the safety of the infra-thin, we can touch the spaces not just in the physical, but also in the emotional and psycho-geographic.

13 January – 20 February 2011

Private view: Wednesday 12 January, 6.30-9.30pm

Look far enough, and things will begin to appear more red than you’d expect. Look really far though – past the horizon, past the sun, and past the galaxy, a few million light years away. Look through a telescope strong enough, look at the distant starts, and you’ll notice that they glow somewhat red.

What you’re seeing is redshift, a consequence of the same law of physics that causes the pitch of ambulance sirens to change as they pass by our ears at speed. Even if we cannot quite observe redshift with a naked eye, employing instead spectral telescopes, the effect is conclusive proof that the universe is expanding. For some 13.7 billion years, light and matter have been travelling away from us, away from one another. Given time, any two distant bodies will drift even further apart, pulled away into new expanses of space. It is space itself that keeps growing, perhaps counter-intuitively, inflating ‘onto’ itself: where there was nothing, there will be space, and matter will follow.

I will not attempt a scientifically-sound description of the physical world here. Marcin Dudek and Ben Washington do not refer to equations or draw in theory into their work either. They do, however, precisely what physical science has been doing all along: they create models which attempt to describe our world with an appropriate degree of accuracy, and to make predictions on what happens next and what is just our of sight.

In I Will Eat This Sleepy Town, Washington’s stars mix with the dirt beneath our feet. The aerial has a dual meaning here: Robert Peston, agent of the apocalypse, hangs in a blue sky watching over the domain, bridges are built from nowhere and to nowhere, and a set of extinguished television screens shines the brightest. The works bring together elements that should not reasonably coexist – the high and the low, the stable and the temporary, the natural and the man-made.

These models start off as prototypes of fantasy realities. Walking amongst the sculptures is perhaps akin to playing a mid-1990s computer game: surfaces of objects, although geometrically correct, are rendered in simplified textures of MDF and laminate, and the level of detail in them alters between the raster and the vector.

Such shifts in scale, matter and content are mirrored in Washington’s working method. The sculptures need to be assembled element by element, and at each stage a delicate balance is found before the subsequent layer can be drawn. This stands at odds with our usual experience of the world, in which all elements appear at once, set in their ways before we become aware of them. With his selective attention to detail, and the luxury of distance, Washington allows us to live out his game, and have all the elements of the model in our field of vision at the same time.

Where Washington takes the bird’s eye view, Marcin Dudek’s tunnel installations are an exploration of the ‘fundamental’ mechanisms of the universe. Confronting his quotidian surroundings, the artist decided to find the new and the unexplained below ground and behind walls. What lies behind the next layer of rock or in the next cavity is unknown, but the directions Dudek takes in his dig soon form a diagram, and elements underground and at the surface become connected in a complex network.

Marcin Dudek, Will Eat This Sleepy Town, 2011

adhesive tape, cellophane, video projections

In I Will Eat This Sleepy Town, Dudek has unearthed a tunnel that leads us across the gallery in a peculiar and convoluted path. This construction, made from little more than packaging tape, becomes an imposing and solid conduit for our movement and thought from the surface to the antipodean interior. Preparing us for the journey is a carbon-copy book of Earth itself: Strata (2010) turns the elements of subsurface into knowledge, making connections between the Chilean miners’ rescue of October 2010 and space rockets. At the turn of his tunnel, Dudek has placed a video trap – a false triumph, a source of artificial light. Propelled further, we make our way to the end, finding that the helical descent into the ground has led us right back to the surface.

mixed media on carbon paper, 20x15cm, 144 pages

This self-referring network, although it may appear arbitrary, is no less logical than the bonds between Ben Washington’s individual sculptures. Dudek has practiced creating this lattice on paper and on canvas, in works like Diagram or Verofragments (both 2007). The tunnels are an extended version of the painting works – in which the canvas itself is three-, if not four-dimensional. The confusing dimensionality is perhaps caused by the fact that Dudek’s installation is peculiar Möbius strip – an object in which the inside and outside are on the same surface. Emerging from the underpass, we see its exterior, a dense, sticky wall that gives no sense of liberation and opens no space.

PVC on paper, 13x18cm

DUD002

An earlier work helps us position ourselves in the clear. Pumping Station (2008) led Dudek to twenty-four railway terminals across Europe. The journey itself created a map of human transits, and in each location, the artist installed a temporary public sculpture made of rubber bicycle tubes, entangled and pumped up to different shapes and pressures. While the appearance of the conduit changed with time and location, the relationship between the external and internal surfaces of the object remained the same, much like in the parcel-tape, walk-in cylinder in I Will Eat This Sleepy Town.

installation view at Gare TGV Liège, Beligium

What connects Washington and Dudek is their interest in defining spaces and creating a set of geometrical parameters that describe our own position. Both know that what they create are only models, and seek out the limits at which the predictions are no longer reliable. This state of uncertainty yet again mirrors the physicist’s view of the universe, in which Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle limits the precision with which we can measure the present state and trajectory of any object.

This restriction notwithstanding, the artists are able to tell us about the boundaries and surfaces we encounter. Marcin Dudek’s video works like Fair Play (2008), in which a tennis ball is repeatedly bounced from surfaces soft and solid in the big top of Frieze Art Fair in Regent’s Park. The artist sends a probe to the limits of (temporary and fictional) space and awaits its return. Another video work, Axis (2010) is a virtual measurement of the lengths, widths and heights of a building, all performed with tape that has no scale. The data collected is unquantifiable, and we interpret it intuitively; the tunnel installation in I Will Eat This Sleepy Town brings us even closer to the illusory object Dudek is trying to describe, forcing us to touch and be led along its very shell.

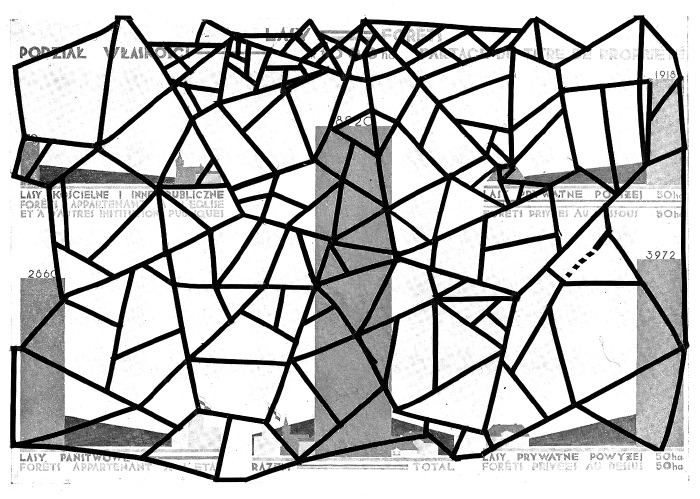

Ben Washington’s sculptures like Advanced Military Layers, which reproduces in miniature a fragment of the Moon’s surface using NASA’s altimetry data, allow us to orbit around the planetary shell. Presented on a Formica-covered office table, an everyday surface of our own, this sculpture places the diametrically different order within our comprehension, rendering both illusory and unreliable. In The Division of a County (2009), a Mars mountainscape, moulded from paper, hangs only feet above our ground, balancing on a less-than stable ladder. Physical elements of this work have found their way into I Will Eat This Sleepy Town, and act as a distant reference point for the remaining works.

Washington’s early collage works demonstrate the artist’s desire to assume different points of view. The constructions appear to contain designs for space ships and launch pads, pylons and ladders, in a way reminiscent of the uncanny accuracy with which Leonardo’s cartoons contained blueprints for helicopters and bicycles. The artist demonstrated his commitment to exploring distance in Apollo 11, when he had a galactic map showing the way to Earth tattooed on his back. In his sculpture, Washington uses his elevated position to look from without, but enlarges and brings closer parts of the landscape, so that the distant and the immediate are ours to touch.

I Will Eat This Sleepy Town brings together the perspectives of looking from the inside and outside, and it may not be clear whether Washington’s and Dudek’s works are prototypes or replicas – the origins or the products of matter. The artists’ two perspectives, however, allow us to choose our own observation points, and to witness the redshift – proof that the universe we live in is expanding – for ourselves without having to arm our senses with apparatus, but through thought alone.

Waterside Project Space is supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, and the exhibition by the Polish Cultural Institute, Austrian Cultural Forum, and Tesa Tapes. We would like to thank the artists, Peter Meikl, Anna Tryc-Bromley, Agnieszka Marszewska, Karolina Kołodziej, Paulina Latham, Jeremy Smith. Mariza Tschali, Rauri Watson, Duncan Ball, Mathilde Stone. We gratefully acknowledge the support of Mr James Ellery and Wonder.

|

|

||